The Buffalo Soldiers

by Linda Allen B. Hollis

Author's Note:

From the time I was a little girl, I listened with relish as my mother shared the stories of my great grandfather, Major George W. Ford's exploits as an original member of the 10th Cavalry, Unit L, also known as the famed Buffalo Soldiers. Official reports state that the 10th regiment were poorly fed, equipped, sheltered, and that they received the harshest of discipline from their officers. My great grandfather served his country under the worst conditions, often receiving cruel and unfair treatment because of his race. Yet, despite the difficult circumstances, Major George Ford showed fortitude and courage - characteristics that many of his compatriots held as they helped tame the Western frontier. Major Ford did two tours with the 10th Calvary. He was a Quartermaster Sergeant when he was honorably discharged on September 11, 1876. He was commended in General Orders No. 53, Series 1874, Fort Sill "for acts of good judgement and gallantry in action." His commanding officer wrote on his discharge papers, "character excellent, good and faithful soldier." At the time of his death, Major George W. Ford was the last, living survivor of the original 10th Calvary. This essay is dedicated to him and those other unsung African American heroes who served with him.

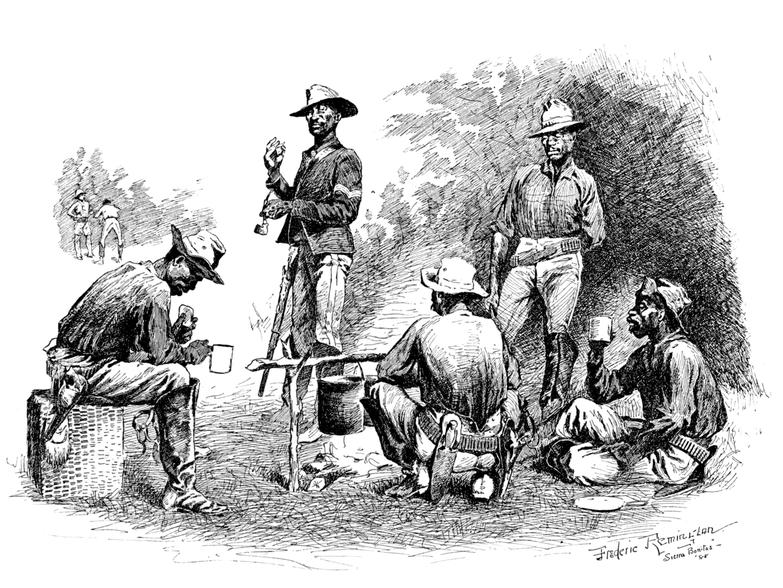

During the Civil War, more than 200,000 African Americans participated in the fight to preserve the Union and bring an end to the institution of slavery. By the time the war ended in 1865, over thirty-eight thousand of these brave men had lost their lives in the fight for freedom. On July 28, 1866, the 39th Congress passed legislation that allowed black soldiers to formally enlist in the United States Army. The soldiers were to serve a five-year term for thirteen dollars a month. The first black contingents consisted of six regiments - the 9th & 10th Cavalries, and the 38th, 39th, 40th, and 41st Infantry Regiments. The African American troops put in long, tiring days learning to become soldiers. At 5:20 a.m. they rose from their barracks and spent the day either on guard duty, practicing military drills, or grooming and exercising their horses. After several long, arduous weeks the new black recruits were ready to defend the West. It was their difficult duty to try to enforce peace between the settlers and the Southern Cheyenne, Kiowas, Comanches, Apaches, and the Arapahos that formed the Confederated Tribes.

During the Civil War, more than 200,000 African Americans participated in the fight to preserve the Union and bring an end to the institution of slavery. By the time the war ended in 1865, over thirty-eight thousand of these brave men had lost their lives in the fight for freedom. On July 28, 1866, the 39th Congress passed legislation that allowed black soldiers to formally enlist in the United States Army. The soldiers were to serve a five-year term for thirteen dollars a month. The first black contingents consisted of six regiments - the 9th & 10th Cavalries, and the 38th, 39th, 40th, and 41st Infantry Regiments. The African American troops put in long, tiring days learning to become soldiers. At 5:20 a.m. they rose from their barracks and spent the day either on guard duty, practicing military drills, or grooming and exercising their horses. After several long, arduous weeks the new black recruits were ready to defend the West. It was their difficult duty to try to enforce peace between the settlers and the Southern Cheyenne, Kiowas, Comanches, Apaches, and the Arapahos that formed the Confederated Tribes.

Many black men joined the army hoping to gain the respect and equality they never received as slaves and rarely as freedmen. But the abolition of slavery, did little to change the prejudices that America held against African Americans. The Army practiced segregation and maintained separate barracks for the white and black troops. Military officials believed that blacks lacked the needed skills and experience to command, so the regiments were put under the control of White officers. Colonel Edward Hatch was put in charge of the 9th Cavalry Regiment, which was assigned to the military division of the Gulf under the command of General Phillip Sheridan. Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson led the 10th Cavalry Regiment, which was assigned to the military division of Missouri under the command of General William T. Sherman.

Many black men joined the army hoping to gain the respect and equality they never received as slaves and rarely as freedmen. But the abolition of slavery, did little to change the prejudices that America held against African Americans. The Army practiced segregation and maintained separate barracks for the white and black troops. Military officials believed that blacks lacked the needed skills and experience to command, so the regiments were put under the control of White officers. Colonel Edward Hatch was put in charge of the 9th Cavalry Regiment, which was assigned to the military division of the Gulf under the command of General Phillip Sheridan. Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson led the 10th Cavalry Regiment, which was assigned to the military division of Missouri under the command of General William T. Sherman.

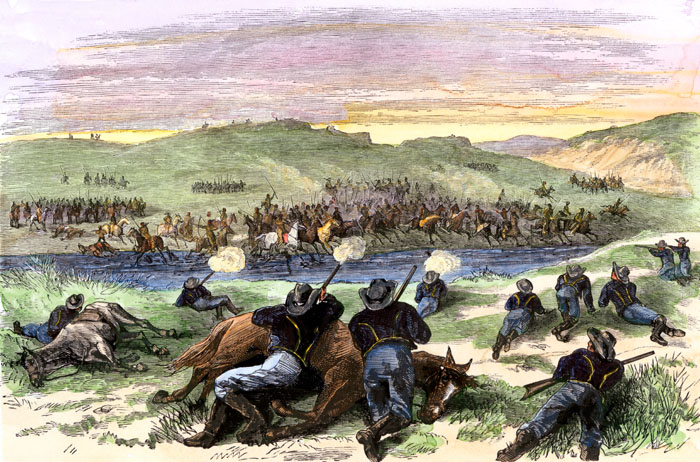

The 9th and 10th Cavalries' service to the country was invaluable, but went largely unrecognized. They were faced with the task of subduing rustlers, outlaws, Mexican revolutionaries, and Native Americans determined to protect their territory. Their assignments took African American soldiers over some of the most rugged and inhospitable country in the western United States as they escorted wagon trains and stagecoaches, built forts and roads, installed telegraphs lines and mapped areas of uncharted country.

The 9th and 10th Cavalries' service to the country was invaluable, but went largely unrecognized. They were faced with the task of subduing rustlers, outlaws, Mexican revolutionaries, and Native Americans determined to protect their territory. Their assignments took African American soldiers over some of the most rugged and inhospitable country in the western United States as they escorted wagon trains and stagecoaches, built forts and roads, installed telegraphs lines and mapped areas of uncharted country.

The black regiments quickly won the respect of their opponents. Around 1868, the Cheyenne and Comanche began to refer to the black cavalry troops of the 9th and 10th as the "Buffalo Soldiers." No one is sure how the name arose, but many believed it was because the Native Americans saw a similarity between the hair of the black soldier and that of the buffalo. The buffalo was also a sacred animal to the Native Americans, and it was a fact that they considered the black troops courageous when met in battle. The troops of the 9th and 10th Regiments accepted their new name with pride and included a buffalo as part of the regimental crest on their uniforms. Many of the soldier's had a change of thought process during their tenure, including George Ford. They began to understand the Native tribes struggle and the despair that they faced with the overwhelming forces of the U.S. Cavalry. They were losing their freedom, fighting for the land of their ancestors, and were consdiered savages just like the black man.

The black regiments quickly won the respect of their opponents. Around 1868, the Cheyenne and Comanche began to refer to the black cavalry troops of the 9th and 10th as the "Buffalo Soldiers." No one is sure how the name arose, but many believed it was because the Native Americans saw a similarity between the hair of the black soldier and that of the buffalo. The buffalo was also a sacred animal to the Native Americans, and it was a fact that they considered the black troops courageous when met in battle. The troops of the 9th and 10th Regiments accepted their new name with pride and included a buffalo as part of the regimental crest on their uniforms. Many of the soldier's had a change of thought process during their tenure, including George Ford. They began to understand the Native tribes struggle and the despair that they faced with the overwhelming forces of the U.S. Cavalry. They were losing their freedom, fighting for the land of their ancestors, and were consdiered savages just like the black man.

The Buffalo soldiers found it less easy to gain the respect of the white settlers whom they were sent to protect. So soon after the Civil War and the end of slavery, many whites still believed blacks to be inferior and begrudged owing any dept of gratitude to them. Yet, the black troops perservered.

The Buffalo soldiers found it less easy to gain the respect of the white settlers whom they were sent to protect. So soon after the Civil War and the end of slavery, many whites still believed blacks to be inferior and begrudged owing any dept of gratitude to them. Yet, the black troops perservered.

The Buffalo Soldiers didn't learn all their lessons on the battlefield, but their self pride grew as they experienced the iron discipline of the frontier army. They learned to accept danger and death as constant companions. Not all of the Buffalo Soldiers could handle the rigors of military life. The desertion rate for enlisted personnel was approximately 25 percent. Some of the new black troopers developed a quick aversion for the army and took off without a "by your leave." Others deserted after minor infractions brought about immediate and harsh punishment. Still, desertions among white regiments were roughly three times greater than those among black units.

The Buffalo Soldiers didn't learn all their lessons on the battlefield, but their self pride grew as they experienced the iron discipline of the frontier army. They learned to accept danger and death as constant companions. Not all of the Buffalo Soldiers could handle the rigors of military life. The desertion rate for enlisted personnel was approximately 25 percent. Some of the new black troopers developed a quick aversion for the army and took off without a "by your leave." Others deserted after minor infractions brought about immediate and harsh punishment. Still, desertions among white regiments were roughly three times greater than those among black units.

The black regiments served from 1866 to 1898 and for decades, African American troops were the most effective troops on the Western frontier. But even all the heroic deeds that the Buffalo Soldiers performed could not wipe out the poison of racial prejudice. For decades their contributions to the nation went virtually unnoticed.

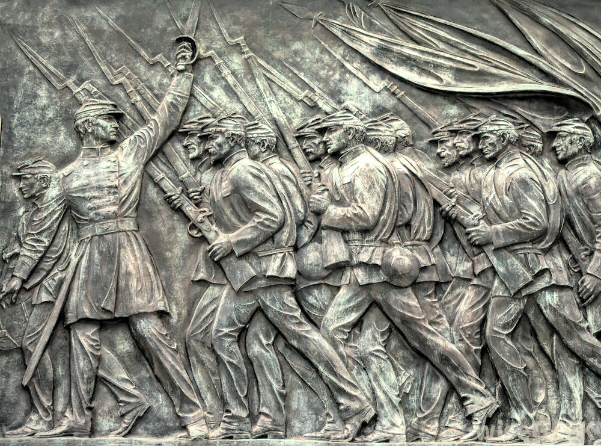

Over the last several decades a new appreciation for the Buffalo Soldiers has emerged. The United States is beginning to recognize the bravery and patriotism of the black men who served in the West - and their example is one in which we can all take pride. In July 1990, General Colin Powell, Secretary of State under the Bush administration, dedicated a memorial at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to the Buffalo Soldiers. He stated, "The Buffalo Soldiers are an everlasting symbol of man's ability to overcome - an everlasting symbol of human courage in the face of all obstacles and dangers."

Over the last several decades a new appreciation for the Buffalo Soldiers has emerged. The United States is beginning to recognize the bravery and patriotism of the black men who served in the West - and their example is one in which we can all take pride. In July 1990, General Colin Powell, Secretary of State under the Bush administration, dedicated a memorial at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to the Buffalo Soldiers. He stated, "The Buffalo Soldiers are an everlasting symbol of man's ability to overcome - an everlasting symbol of human courage in the face of all obstacles and dangers."

Major George Ford's life as a Buffalo Soldier is detailed in, "I Cannot Tell a Lie: The True Story of George Washington's African American Descendants." For more information about the Buffalo Soldiers, check out www.Buffalosoldiers.net.

- Login to post comments